Mar 3rd 2016

Piston ring seating problems?

Almost all smoking or seized pistons at break-in can be traced to improper break-in procedure.

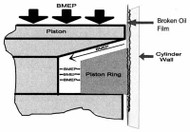

This graphic shows gas pressure (brake mean effective pressure) from the combustion process getting behind the ring and force it against the cylinder wall during break-in. The cylinder barrel is the only point on the engine where metal-to-metal contact is desired at any time. However, it’s only desirable during break-in and not during the rest of the engine’s life. This metal-to-metal contact is necessary to “match wear” the rings to the cylinder walls, something that’s required for good compression and long top-end life.

The ring seating process is accomplished by actual metal-to-metal contact between the ring and the cylinder wall. The ring’s job is to seal all the gases it can on the top side of the piston from escaping to the bottom side of the piston and into the crankcase.

To accomplish this, the ring must match the contour of the cylinder barrel along the ring’s full diameter and width. The cylinder barrel must also do some wearing to have a consistent contour along the stroke of the ring. This will enable heat to dissipate quickly through the rings, keeping the rings and piston cool. This also makes for a tightly sealed combustion chamber, which makes for a healthy, efficient and powerful engine and an acceptable level of oil consumption that’s a trade-off between wear reduction and good compression sealing. Piston rings transfer heat to the cylinder wall. Without good cylinder to ring contact the piston will continue to expand in the bore. At some point the piston will stick or seize.

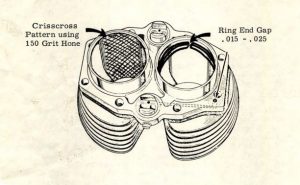

The down side to improper break-in are seized pistons. Modern oil’s film strength can be so strong that it can keep the rings from ever contacting the cylinder. Although this is a good feature once the rings are seated, some contact has to occur with grey cast iron rings during break-in. Some people have gone to the trouble to learn how to use modern ductile iron and steel rings in British bikes. That takes a lot of time and money. Most of you will be using the old fashion grey cast iron rings. These rings are not lapped round and true at the factory. They are designed so that the final finishing is in the cylinder. Thus they require a coarser cylinder finish than a modern ring. This actually requires that during break-in the ring come in contact with the cylinder wall. Most grey cast iron rings specify a 150 to 220 grit, with 180 being what we recommend. Recommended cylinder to piston clearance of .0015 thousandths per inch of bore works out to .0035 to .005 thousands. We have our cylinders set up at .0045 when running cast JCC pistons. Forged pistons will require a larger clearance. Best to contact the manufacturer if possible.

Modern oil, and I am not talking about pure synthetics, do not allow this to happen and can hold the ring’s face off the cylinder wall preventing break-in. To make a long story short, many have gone to alternative oils and break-in procedures. Lacking break-in oil many of us have resorted to what is commonly called dry assembly.

We like to call it drier assembly. That is where we wash the cylinder in hot soapy water, let it dry and run a lint free cloth thru the bore. (Hot soapy water is much better at removing hone debris than solvent).We then lube every thing else: camshaft, tappets, and a drop or so on the thrust faces of the pistons only, leaving the rings and cylinder dry. When installing piston rings any writing or markings face upwards toward the cylinder head. The same does if the rings have an inside beveled edge. If there is any doubt it is best to check with the maker if no instructions were included. Note factory ring end gap is no longer applicable. All new production rings have end gap specifications of (.015-.028). There should only be real concern if there is no ring end gap. In Oct 69 Triumph actually released a service bulletin changing the specifications. ring end gap service bulletin pdf

It is highly recommended that the oil be changed and “running in oil” be used with your new piston rings. Use a 30 weight non-detergent oil, available at any auto parts store. Do not use any specialty oils or Castro GTX. Your piston rings will never seat. Modern oil is a lot different than the oils out only a decade ago. Oils continue to change due to more stringent emission standards, catalytic converters, and friction modifying molecules added for improving efficiency (energy conserving oils). In experience these modern oils lead to seizure and excessive smoking.

Once assembled we verify oil pressure turning the motor over with the plugs out, and once oil is circulating we start the motor and go for a ride. Be ready to go, don’t let the engine sit idling. Accelerate rather briskly through the gears. Keep the rpms between 3500-500 while accelerating. Don’t lug or bog the engine to be easy on it. The object is to seat the new rings in the cylinder. Heat generated by the combustion process is transferred to the cylinder by the rings. In a new bore this process is inhibited until the rings seat. It is the combustion pressure behind the ring which forces the rings into contact with the cylinder wall. Therefore brisk acceleration actually helps heat transfer and promotes longer engine life. After a few acceleration stints shut off the machine and let it cool down for 10 minutes or so. Repeat the process a few times and then park the machine over night until completely cold. Recheck all base nuts and head bolts. Ride the motorcycle as normal for the first 300 miles avoiding long stretches of constant engine RPM. Re-torque all top end fasteners after 300 miles and reset the valve clearances. At 500 mile change the oil to Shell Rotella (Diesel oil) it still contains ZDDP for flat tappet engines. Recheck fasteners again at 1000 miles.